Plastic surgery seems to be an invention of the modern age. The desire to attain physical beauty is no doubt one of the factors that has contributed to the popularity of this procedure. Apart from cosmetic reasons, plastic surgery is also carried out for reconstructive purposes. Yet, plastic surgery has been around longer than most people realize. One of the earliest instances of plastic surgery can be found in the Sushruta Samhita, an important medical text from India.

The Sushruta Samhita is commonly dated to the 6th century B.C., and is attributed to the physician Sushruta (meaning ‘very famous’ in Sanskrit). The Sushruta Samhita’s most well-known contribution to plastic surgery is the reconstruction of the nose, known also as rhinoplasty. The process is described as such:

The portion of the nose to be covered should be first measured with a leaf. Then a piece of skin of the required size should be dissected from the living skin of the cheek, and turned back to cover the nose, keeping a small pedicle attached to the cheek. The part of the nose to which the skin is to be attached should be made raw by cutting the nasal stump with a knife. The physician then should place the skin on the nose and stitch the two parts swiftly, keeping the skin properly elevated by inserting two tubes of eranda (the castor-oil plant) in the position of the nostrils, so that the new nose gets proper shape. The skin thus properly adjusted, it should then be sprinkled with a powder of licorice, red sandal-wood and barberry plant. Finally, it should be covered with cotton, and clean sesame oil should be constantly applied. When the skin has united and granulated, if the nose is too short or too long, the middle of the flap should be divided and an endeavor made to enlarge or shorten it.

A statue dedicated to Sushruta at the Patanjali Yogpeeth institute in Haridwar

A statue dedicated to Sushruta at the Patanjali Yogpeeth institute in Haridwar. Wikimedia, CC

A statue dedicated to Sushruta at the Patanjali Yogpeeth institute in Haridwar. Wikimedia, CCOther contributions of the Sushruta Samhita towards the practice of plastic surgery include the use of cheek flaps to reconstruct absent ear lobes, the use of wine as anesthesia, and the use of leeches to keep wounds free of blood clots.

It may also be pointed out that the Sushruta Samhita is also one of the foundational texts of the Ayurveda, the traditional medical system of India. Therefore, the Sushruta Samhita contains more than just the description of plastic surgery procedures. The Sushruta Samhita, in its existing form, is said to consist of 184 chapters containing descriptions of 1,120 illnesses, as well as several hundred types of drugs made from animals, plants and minerals. Furthermore, the Sushruta Samhita also contains 300 surgical procedures divided into 8 categories, and 121 different types of surgical instruments.

In addition, Sushruta taught that in order to be a good doctor, one should possess medical knowledge in both its theoretical and practical forms. To this end, he devised various experimental modules (these can also be found in the Sushruta Samhita) for his students to practice the different surgical procedures contained in his medical text. For instance, ‘incision’ and ‘excision’ were to be practiced on vegetables and leather bags filled with mud of different densities, ‘probing’ on moth-eaten wood or bamboo, and ‘puncturing’ on the veins of dead animals and lotus stalks.

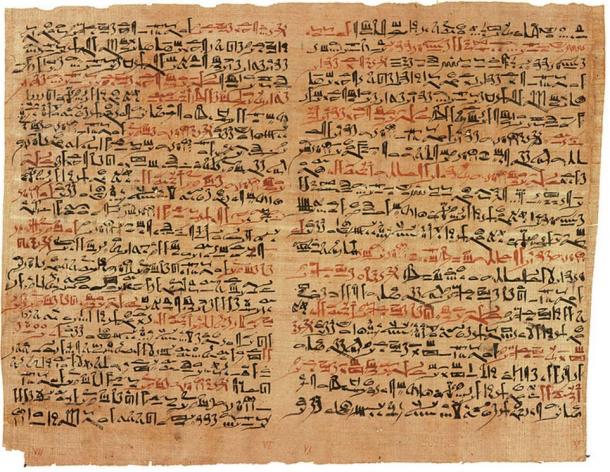

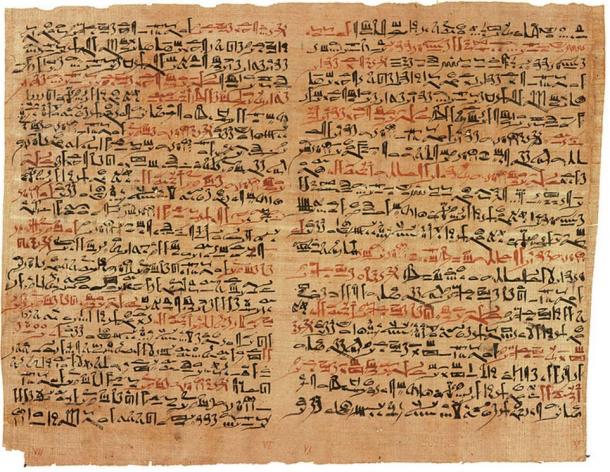

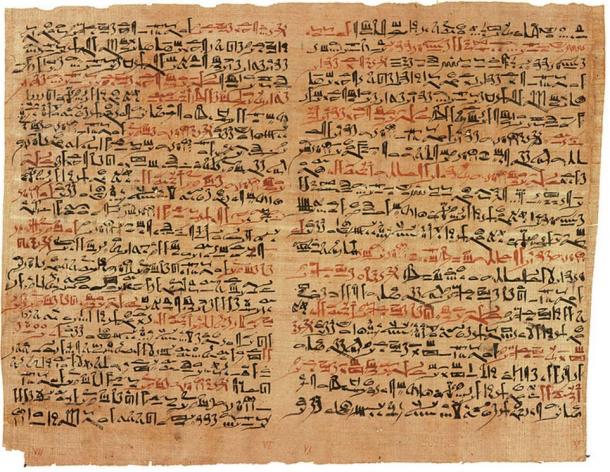

The Edwin Smith Papyrus - the world's oldest surviving surgical document

The Edwin Smith Papyrus - the world's oldest surviving surgical document - details practical treatments to illnesses and injury, but does not mention plastic or reconstructive surgery like the Sushruta Samhita. Written in hieratic script in ancient Egypt around 1,600 B.C. Public Domain

The Edwin Smith Papyrus - the world's oldest surviving surgical document - details practical treatments to illnesses and injury, but does not mention plastic or reconstructive surgery like the Sushruta Samhita. Written in hieratic script in ancient Egypt around 1,600 B.C. Public DomainDuring the 8th century A.D., the Sushruta Samhita was translated into Arabic by a person known as Ibn Abillsaibial. This Arabic translation, known as the Kitab Shah Shun al-Hindi or the Kitab i-Susurud, eventually made its way to Europe by the end of the medieval period. In Renaissance Italy, the Branca family of Sicily, and the Bolognese doctor, Gasparo Tagliacozzi, were familiar with the surgical techniques found in the Sushruta Samhita. Nevertheless, European mastery of plastic surgery, and surgery in general, only came several centuries later. Meanwhile, in India the Suhruta Samhita has made Indian physicians highly skilled in surgical practice. In 1794, an account was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine of London describing the use of plastic surgery used to reconstruct the nose of a Maratha cart-driver mutilated by the soldiers of Tippu Sultan. The procedure was similar to that taught by Sushruta, though instead of grafting skin from the cheek, skin from the forehead was grafted instead. In a way, this shows that medical knowledge in India was not a dead subject, and that innovations could be made to further refine surgical techniques from the 6th century B.C. Thus, Sushruta’s procedure for rhinoplasty was introduced to the West in this manner.

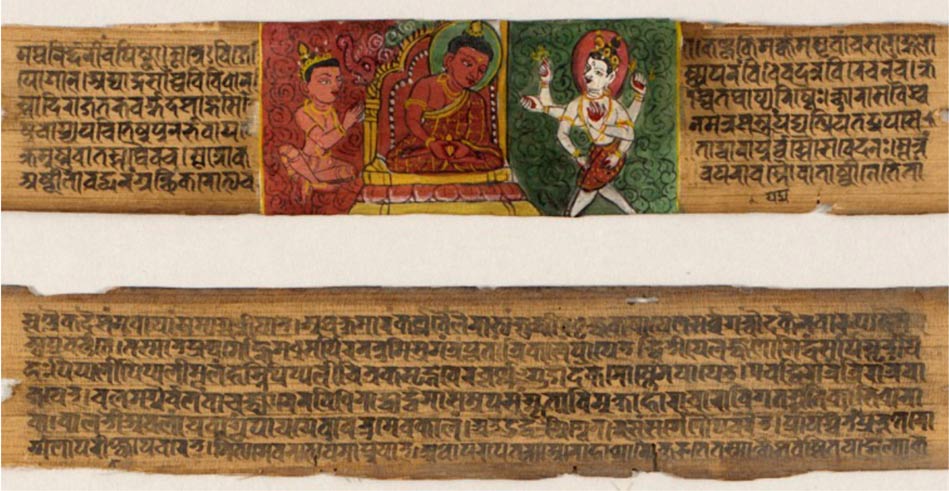

Featured image: Detail, The Susruta-Samhita (A Treatise on Ayurvedic Medicine) Public Domain

- fonte:

The Sushruta Samhita and Plastic Surgery in Ancient India, 6th century B.C.

Plastic

surgery seems to be an invention of the modern age. The desire to

attain physical beauty is no doubt one of the factors that has

contributed to the popularity of this procedure. Apart from cosmetic

reasons, plastic surgery is also carried out for reconstructive

purposes. Yet, plastic surgery has been around longer than most people

realize. One of the earliest instances of plastic surgery can be found

in the Sushruta Samhita, an important medical text from India.

The Sushruta Samhita is commonly dated to the 6th century B.C., and is attributed to the physician Sushruta (meaning ‘very famous’ in Sanskrit). The Sushruta Samhita’s most well-known contribution to plastic surgery is the reconstruction of the nose, known also as rhinoplasty. The process is described as such:

It may also be pointed out that the Sushruta Samhita is also one of the foundational texts of the Ayurveda, the traditional medical system of India. Therefore, the Sushruta Samhita contains more than just the description of plastic surgery procedures. The Sushruta Samhita, in its existing form, is said to consist of 184 chapters containing descriptions of 1,120 illnesses, as well as several hundred types of drugs made from animals, plants and minerals. Furthermore, the Sushruta Samhita also contains 300 surgical procedures divided into 8 categories, and 121 different types of surgical instruments.

In addition, Sushruta taught that in order to be a good doctor, one should possess medical knowledge in both its theoretical and practical forms. To this end, he devised various experimental modules (these can also be found in the Sushruta Samhita) for his students to practice the different surgical procedures contained in his medical text. For instance, ‘incision’ and ‘excision’ were to be practiced on vegetables and leather bags filled with mud of different densities, ‘probing’ on moth-eaten wood or bamboo, and ‘puncturing’ on the veins of dead animals and lotus stalks.

Featured image: Detail, The Susruta-Samhita (A Treatise on Ayurvedic Medicine) Public Domain

The Sushruta Samhita is commonly dated to the 6th century B.C., and is attributed to the physician Sushruta (meaning ‘very famous’ in Sanskrit). The Sushruta Samhita’s most well-known contribution to plastic surgery is the reconstruction of the nose, known also as rhinoplasty. The process is described as such:

The portion of the nose to be covered should be first measured with a leaf. Then a piece of skin of the required size should be dissected from the living skin of the cheek, and turned back to cover the nose, keeping a small pedicle attached to the cheek. The part of the nose to which the skin is to be attached should be made raw by cutting the nasal stump with a knife. The physician then should place the skin on the nose and stitch the two parts swiftly, keeping the skin properly elevated by inserting two tubes of eranda (the castor-oil plant) in the position of the nostrils, so that the new nose gets proper shape. The skin thus properly adjusted, it should then be sprinkled with a powder of licorice, red sandal-wood and barberry plant. Finally, it should be covered with cotton, and clean sesame oil should be constantly applied. When the skin has united and granulated, if the nose is too short or too long, the middle of the flap should be divided and an endeavor made to enlarge or shorten it.

A statue dedicated to Sushruta at the Patanjali Yogpeeth institute in Haridwar. Wikimedia, CC

Other contributions of the Sushruta Samhita towards the

practice of plastic surgery include the use of cheek flaps to

reconstruct absent ear lobes, the use of wine as anesthesia, and the use

of leeches to keep wounds free of blood clots.It may also be pointed out that the Sushruta Samhita is also one of the foundational texts of the Ayurveda, the traditional medical system of India. Therefore, the Sushruta Samhita contains more than just the description of plastic surgery procedures. The Sushruta Samhita, in its existing form, is said to consist of 184 chapters containing descriptions of 1,120 illnesses, as well as several hundred types of drugs made from animals, plants and minerals. Furthermore, the Sushruta Samhita also contains 300 surgical procedures divided into 8 categories, and 121 different types of surgical instruments.

In addition, Sushruta taught that in order to be a good doctor, one should possess medical knowledge in both its theoretical and practical forms. To this end, he devised various experimental modules (these can also be found in the Sushruta Samhita) for his students to practice the different surgical procedures contained in his medical text. For instance, ‘incision’ and ‘excision’ were to be practiced on vegetables and leather bags filled with mud of different densities, ‘probing’ on moth-eaten wood or bamboo, and ‘puncturing’ on the veins of dead animals and lotus stalks.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus - the world's oldest

surviving surgical document - details practical treatments to illnesses

and injury, but does not mention plastic or reconstructive surgery like

the Sushruta Samhita. Written in hieratic script in ancient Egypt around

1,600 B.C. Public Domain

During the 8th century A.D., the Sushruta Samhita was translated into Arabic by a person known as Ibn Abillsaibial. This Arabic translation, known as the Kitab Shah Shun al-Hindi or the Kitab i-Susurud,

eventually made its way to Europe by the end of the medieval period. In

Renaissance Italy, the Branca family of Sicily, and the Bolognese

doctor, Gasparo Tagliacozzi, were familiar with the surgical techniques

found in the Sushruta Samhita. Nevertheless, European mastery

of plastic surgery, and surgery in general, only came several centuries

later. Meanwhile, in India the Suhruta Samhita has made Indian physicians highly skilled in surgical practice. In 1794, an account was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine of London

describing the use of plastic surgery used to reconstruct the nose of a

Maratha cart-driver mutilated by the soldiers of Tippu Sultan. The

procedure was similar to that taught by Sushruta, though instead of

grafting skin from the cheek, skin from the forehead was grafted

instead. In a way, this shows that medical knowledge in India was not a

dead subject, and that innovations could be made to further refine

surgical techniques from the 6th century B.C. Thus, Sushruta’s procedure for rhinoplasty was introduced to the West in this manner.Featured image: Detail, The Susruta-Samhita (A Treatise on Ayurvedic Medicine) Public Domain

'Cleopatra’s Milk Bath', contemporary mosaic by Irel.

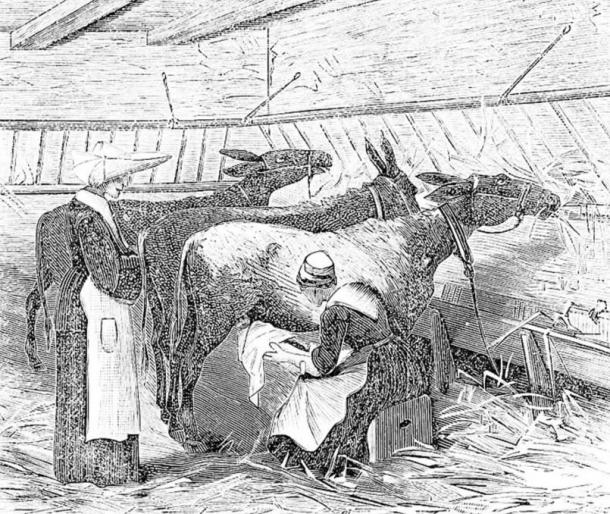

'Cleopatra’s Milk Bath', contemporary mosaic by Irel. Nurse holding a baby to suckle directly from a donkey at the hospital for assisted children in Paris, 1882-1883. (Wikimedia Commons)

Nurse holding a baby to suckle directly from a donkey at the hospital for assisted children in Paris, 1882-1883. (Wikimedia Commons) Donkey milk is still used throughout the world for its many health benefits. Source: BigStockPhoto

Donkey milk is still used throughout the world for its many health benefits. Source: BigStockPhoto