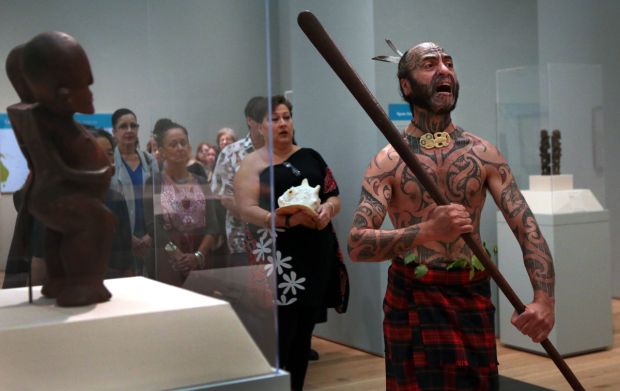

Maori artist George Nuku leads guests and staff into the St. Louis Art Museum, performing a ceremony for 'Atua: Sacred Gods from Polynesia' on Wednesday, Oct. 8, 2014. "I take this opportunity to salute the ground we stand on," said Nuku, who performed the rituals to honor Polynesian ancestors and connect them with the art. The exhibit opens to visitors on Sunday. Photo by Robert Cohen, rcohen@post-dispatch.com

Related Galleries

St. Louis Art Museum's 'Atua' explores Polynesia

A team of St. Louis Art Museum officials and Washington University doctors hope CT scans will open window to health, death and, perhaps, provi… Read more

'Atua: Sacred Gods From Polynesia'

When • Through Jan. 4 (10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Friday, closed Monday)

Where • St. Louis Art Museum, 1 Fine Arts Drive, Forest Park How much • $12 adults, $10 seniors and students, $6 children ages 6 to 12; members and children under 6 free

More info • 314-721-0072; slam.org

It was not your usual preview at the St. Louis Art Museum. Then again, “Atua: Sacred Gods from Polynesia” is not your usual exhibition.

For one thing, there was George Nuku, clad only in a simple kilt of unhemmed Scottish tartan, with feathers in his topknot, elaborate tattoos on his face, torso and legs, and carrying a taiaha, a carved wooden spear.

An hour before the doors officially opened on Wednesday morning, Nuku, 50, a Maori (and Scots, and German) artist from New Zealand, walked out the doors of the East Building. Moving in stylized fashion, he walked to the nearest trees, pulled off leavesand inserted them into the fabric around his waist. He saluted the park, and returned, ready to lead a ritual, “a metaphor of giving birth.”

A small crowd of people awaited him. On hand were a half-dozen St. Louisans of Polynesian descent, one a woman carrying a large conch shell. A few members of the staff joined in. Also participating were the exhibition’s curator, Michael Gunn, formerly of the St. Louis Art Museum and now of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, and Nichole Bridges, the museum’s associate curator for the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas.

Then came the rest of the museum’s staff, more than a hundred of them, ready to take part in the ritual. “We are crossing portals, from the world of us to the world of the ancestors, and then back,” Nuku said. “The most important thing is that we are doing it together.”

He started by saluting “the family of the museum, the guardians and custodians of these treasures” and the building itself, that it would stand firmly and protect the objects within. He explained that the woman with the conch would blow it three times, in the way a Maori woman announces that she’s ready to deliver. Nuku, a warrior, would go out with his spear, cutting the waters: “We’re having a baby this morning, folks.”

The group moved as a body (“No stragglers,” said Nuku) through the exhibit, mostly silent, as he walked at the front like a dancer, lifting his feet as he stepped, declaiming in Maori. “Clear the pathway! Ukuia te ara!”

The exhibition, which was first shown at the National Gallery of Australia, deserves such extraordinary treatment. The images on view are religious objects, statues and reliquaries, and are thought to contain the spirits of ancestors. They range from objects made in the 15th century to a piece that Nuku, a sculptor, was to complete on Saturday. They are visually striking, frequently sophisticated and sometimes linger in the mind’s eye.

Photo gallery of works from 'Atua'

Polynesian culture is largely unknown in North America, once we get past popular images of luaus, the monumental Easter Island statues and the mutiny on H.M.S. Bounty. A little study will both make the scope of this exhibition more impressive and the seeing of it more rewarding.

Polynesia occupies a vast expanse of the South Pacific Ocean, its waters dotted with atolls and archipelagos. Most of its more than 1,000 islands are small; New Zealand comprises more than 103,000 square miles of the 118,000-or-so-square miles of land in Polynesia. It’s shaped like a triangle with a bite taken out of it, with Hawaii at the top, Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the southeast and Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the southwest.

Its people originated in Taiwan and began to spread across the Pacific 3,000 years ago in outriggers, arriving in New Zealand in about 1250. Skilled navigators, they shared a family of languages, a culture and mythology.

The atua are gods, many of them ancestors-turned-deities, beings of the supernatural world known as Te Po. Some of them, including Tangaroa, god of the sea, are found across Polynesia. Others are local. They number in the thousands and have almost as many distinct personalities. Life on an atoll is precarious, death is frequent and the ancestors were often called upon for aid.

When Christian missionaries arrived, Polynesians took to the new religion enthusiastically. Some of the atua were destroyed by missionaries, or, especially, by converts, as heathen idols. Others were given away or taken as souvenirs. Most were lost forever. The atua in the exhibition come from an impressive array of institutions and private collections around the world.

Gunn, a New Zealander, began working on the exhibition when at the St. Louis Art Museum in 1999, “and it went on the books in 2001.” He visited 140 museums and 60 private collections in all, “trying to find pieces we knew something about,” he said in an interview. “If it had a presence that came alive when I was there, then it was a definite candidate. Some pieces had a life of their own.”

After a pair of modern sculptures in traditional style, the galleries are arranged by geography, beginning with Fiji. A group of several hundred islands located about 1,300 miles northeast of New Zealand, it’s technically a part of Melanesia, not Polynesia, but the Polynesians were there first, and they have a strong cultural connection.

Three female figures from Fiji are all different, and all powerful. One of the most appealing figures in the exhibition is a woman with zigzag arms and square-cut eyes, wearing a shell necklace.

The quality of some of the carvings, particularly the “staff gods” from Raratonga in the Cook Islands and assorted figures from Rapa Nui, belies any assumption that this was a primitive society; these are complex and sophisticated works of art. Although some may seem rough at first glance, they have a balance and (to use Gunn’s word) a presence that is arresting.

A pair of figures from Rapa Nui, made of wicker and covered in painted barkcloth, are a little scary at first but engaging on second glance; made by the same artist, they were separated for more than a century and a half before being reunited for this exhibition. A muscular Hawaiian with human hair seems poised to jump out at the viewer.

The outer threshold, or paepae, of a storehouse from New Zealand is elaborately carved with male and female figures, some of them being dragged to their deaths. A kava bowl from the Austral Islands, made to hold a psychoactive drink once used throughout Polynesia, was intricately decorated with a shark-tooth tool. The female figure from Rapa Nui whose head is seen on the exhibition catalogue exudes resigned grief.

Gunn speaks frequently of the “presence” of the atua, and he’s not being metaphorical. Most of the surviving atua are of human beings, and, he says, they still contain human emotions. “The first guy you meet when we come in (the exhibition) lets you know when he likes something or not. It sounds crazy, but when you accept it, it makes sense. I’m a Westerner, and I try to stay rational, but I have to accept things when they happen, at least when there are others there who see (them).” Most of the presences, he says are “not negative but aggressive.”

Reading Gunn’s catalogue helps to put it all into perspective. The exhibition will end its two-stop run in St. Louis; many owners of artifacts were reluctant to part with them long enough to allow them to be shown at a venue in Europe as well as Australia and the United States.

‘Atua: Sacred Gods From Polynesia’

When • Through Jan. 4 (10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Friday, closed Monday)

Where • St. Louis Art Museum, 1 Fine Arts Drive, Forest Park How much • $12 adults, $10 seniors and students, $6 children ages 6 to 12; members and children under 6 free

More info • 314-721-0072; slam.org

• See more photos from the exhibition at stltoday.com/arts.

Sarah Bryan Miller is the

Post-Dispatch’s classical music critic. Follow Bryan on the Culture Club

blog, and on Twitter at @SBMillerMusic.

fonte: @edisonmariotti #edisonmariotti http://www.stltoday.com/entertainment/arts-and-theatre/st-louis-art-museum-explores-important-territory-in-atua-sacred/article_81a5b5e2-b370-562f-beea-bc293e36fd70.html

fonte: @edisonmariotti #edisonmariotti http://www.stltoday.com/entertainment/arts-and-theatre/st-louis-art-museum-explores-important-territory-in-atua-sacred/article_81a5b5e2-b370-562f-beea-bc293e36fd70.html

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário