Ideia surgiu há mais de 100 anos, mas só foi aprovada em 2003.

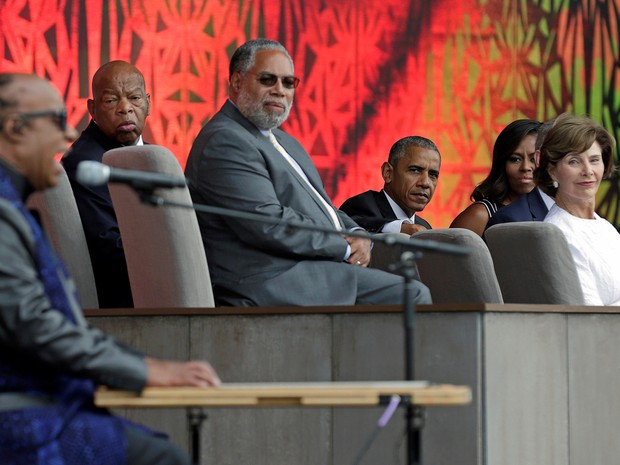

O presidente Barack Obama inaugurou neste sábado o Museu Nacional de História e Cultura Afro-Americana, em Washington. Na cerimônia de inauguração, cortou a fita e inaugurou o museu de 37 mil metros quadrados revestido em bronze, diante de milhares de pessoas.

Museu Afro-americano inaugurado neste sábado (24)

em Washington (Foto: Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP)

em Washington (Foto: Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP)

"Além da suntuosidade do edifício, o que torna esta ocasião tão especial é a rica história que ele abriga", disse Obama durante a cerimônia, da qual participaram personalidades como o cantor Stevie Wonder e a apresentadora de TV Oprah Winfrey.

"A história afro-americana não está separada da nossa grande história americana. Não é a parte inferior da história americana. É parte central da história americana", expressou.

Presidente dos Estados Unidos, Barack Obama

inaugura museu afro-americano em Washington (Foto: Zach Gibson / AFP)

O museu foi concebido originalmente em 1915, quando veteranos da guerra civil americana buscavam uma maneira de homenagear a experiência dos afro-americanos no conflito.

A construção foi finalmente aprovada numa lei assinada pelo ex-presidente George W. Bush em 2003. O prédio tem uma localização privilegiada, próxima à Casa Branca e ao Monumento de Washington, e abriga 34 mil objetos, tendo sido quase a metade deles doados.

Tensão racial

A inauguração acontece em um contexto de forte tensão racial, enquanto cresce a indignação no país diante da morte de negros por policiais. O caso mais recente gerou protestos em Charlotte, Carolina do Norte (sudeste).

Este é o primeiro museu nacional dedicado a documentar as verdades incômodas envolvendo a opressão sistemática sofrida pelos negros no país, ao mesmo tempo em que homenageia o papel da cultura afro-americana.

"Uma visão clara da história pode nos incomodar (...) mas é, precisamente, a partir deste incômodo que aprendemos e crescemos, e aproveitamos o poder coletivo para tornar esta nação perfeita".

Eleito em meio a uma onda de otimismo, em 2008, Obama prometeu unificação, reiterando que não era presidente dos negros, e sim de todos os americanos. Mas seu mandato termina e as pesquisas mostram que a ampla maioria dos americanos vêem as relações inter-raciais como "em geral, ruins".

Os tiroteios recentes em que negros foram mortos pelas polícias de Tulsa (Oklahoma, sudoeste) e Charlotte (Carolina do Norte, sudeste) voltaram a expor os problemas raciais do país.

Stevie Wonder se apresenta na inauguração do Museu Afro-Americano, em Washington (Foto: Yuri Gripas / Reuters)

"Mesmo diante de dificuldades inimagináveis, os Estados Unidos avançaram. E este museu contextualiza os debates do nosso tempo."

"Talvez possa ajudar um visitante branco a compreender o sofrimento e a indignação dos manifestantes em lugares como Ferguson e Charlotte", assinalou.

O museu mostra "que este país, nascido da mudança, este país, nascido de uma revolução, este país, nosso, do povo, este país pode ser melhor", disse o presidente.

"É um monumento, não menos importante do que os outros neste passeio, para o profundo e duradouro amor por este país e os ideais sobre os quais ele foi fundado. Porque nós também somos americanos", assinalou.

Cultura e conhecimento são ingredientes essenciais para a sociedade.

Cultura e conhecimento são ingredientes essenciais para a sociedade.

A cultura e o amor devem estar juntos.

Vamos compartilhar.

A cultura e o amor devem estar juntos.

Vamos compartilhar.

--in

When I walked into the new National Museum of African American History and Culture for a preview last week, my excitement was tempered. I’d heard about the feats of engineering: rooms built around a massive guard tower from Louisiana’s Angola Prison, a Southern Railroad train car and a Tuskegee Airman-flown plane. I’d heard about the big donationsfrom Oprah Winfrey and Michael Jordan. I’d followed the decades-long campaign for real estate and funding that were required to make this new institution a reality. But that was the story of the museum itself. I was worried that the exhibits might fall short of illustrating — panel by panel, artifact by artifact — the story of black America, which is not merely about the biggest names and the best-remembered movements. I was worried about what might have been intentionally left out or inadvertently forgotten.

When I walked into the new National Museum of African American History and Culture for a preview last week, my excitement was tempered. I’d heard about the feats of engineering: rooms built around a massive guard tower from Louisiana’s Angola Prison, a Southern Railroad train car and a Tuskegee Airman-flown plane. I’d heard about the big donationsfrom Oprah Winfrey and Michael Jordan. I’d followed the decades-long campaign for real estate and funding that were required to make this new institution a reality. But that was the story of the museum itself. I was worried that the exhibits might fall short of illustrating — panel by panel, artifact by artifact — the story of black America, which is not merely about the biggest names and the best-remembered movements. I was worried about what might have been intentionally left out or inadvertently forgotten.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture shows a reflection of the Washington Monument on Tuesday, August 9, 2016. The new museum opens to the public on September 24. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

By Blair L.M. Kelley September 22

Blair L.M. Kelley is associate professor of history and assistant dean of Interdisciplinary Studies and International Programs at North Carolina State University.

But my worries were unfounded. The museum succeeds by grappling, in an elegant fashion, with the many strands — sometimes uncomfortable, sometimes uplifting — of African American history, and how closely they’re interwoven with the American experiment from its inception. It tells the stories of black America the way they should be told, the way I, as a historian, strive to tell them: Not an account of black people fitting into American history, but American history told through the black experience.

History, after all, isn’t just curating facts but marshaling the facts of our collective past to help us better understand our present. That’s one of the reasons I wrote “Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson,” to address the misperception that generations of black Americans passively accepted segregation prior to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. My examination of the period when segregation laws were first introduced in the 1840s and 1850s in Northern cities, and then with ubiquity in Southern cities in the decades around the turn of the 20th century, revealed that protest was the norm — and showed a broader truth about the constancy of black struggle in America. Black travelers on trains sued when they were excluded from first-class cars. African American streetcar riders launched boycotts in more than 25 Southern cities between 1900 and 1907.

In the same spirit, the museum works because its artifacts aren’t merely displayed to narrate a tidy through-line of black history’s greatest hits, from Crispus Attucks to Harriet Tubman to Frederick Douglass to Michelle Obama. Rather, its spaces remind us that from before the nation’s beginnings, African Americans have experienced victories and defeats in many times and places, and our traumas have often taken place alongside our triumphs. There’s the exhibit highlighting the people Thomas Jefferson enslaved, with bricks inscribed with their names standing like a wall behind his statue. Around the nation’s third president, author of our Declaration of Independence, stand African American luminaries, such as poet Phillis Wheatley, whom Jefferson dismissed as inferior in his “Notes on the State of Virginia,” and scientist Benjamin Banneker, who challenged Jefferson on race. In the same exhibit you can see shackles designed for a small child; they’re the sort used when people were sold away, just as hundreds of people enslaved by Jefferson were sold on the lawn of Monticello to settle his estate after his death.

This one exhibit takes you from achievement to seemingly insurmountable barriers and back. This isn’t a clean or easy story to tell, but to tell it another way would be wrong, a perpetuation of the too-frequent oversimplification of black history.

This museum’s triumph is that it gives teachers and learners a fresh start at thinking about black life and culture in this country on the same intellectual track as the rest of our nation’s history, rather than as a version that spotlights African Americans as a people apart, feted every February, then relegated to the background.

Yes, some artifacts in some museums are there purely to remind tour groups and summer class trips about milestones in American history. But the African American Museum adds an extra dimension by showcasing lesser-known pieces of black history that tie the narrative together. It shows us that the folks who organized the Niagara, anti-lynching and women’s club movements were just as “woke” to the oppression of white supremacy as the civil rights generation. As you progress through the space you also understand that, as Ella Baker said, black Americans have long been, and should be, demanding “more than a hamburger.” Today’s debate over economic inequality comes to mind when you see the art wall preserved from Resurrection City, a shantytown protest mounted by the Poor People’s Campaign, the last protest initiative organized by Martin Luther King Jr. before his assassination. The striking images from the wall include the command to “tell it like it is”; situating the protest, in other words, in the wider context of the long fight for equality.

The museum’s curators did important work in centering the ordinary and extraordinary people highlighting the stories we know, such as Douglass and King, but placing them alongside artifacts from people we probably have never heard of whose experiences are just as telling. In contrast to the CliffsNotes version of black history that usually focuses on the Great Men, they emphasize women’s experiences with regularity and clarity. A casual observer might miss the panels focused on black female ministers Florence Spearing Randolph, Mary J. Small, Jarena Lee and Julia A.J. Foote. On a first pass, one might not notice that Sojourner Truth is highlighted on a panel with the label “black feminist,” or sense the full import of a panel featuring Maggie Lena Walker and the Independent Order of St. Luke. But in these works, I hope museum-goers absorb the scholarly contributions of female black historians. In reflecting this work, the exhibits consistently tell us more about what we already know and offer nuance about things most Americans have never heard of.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário